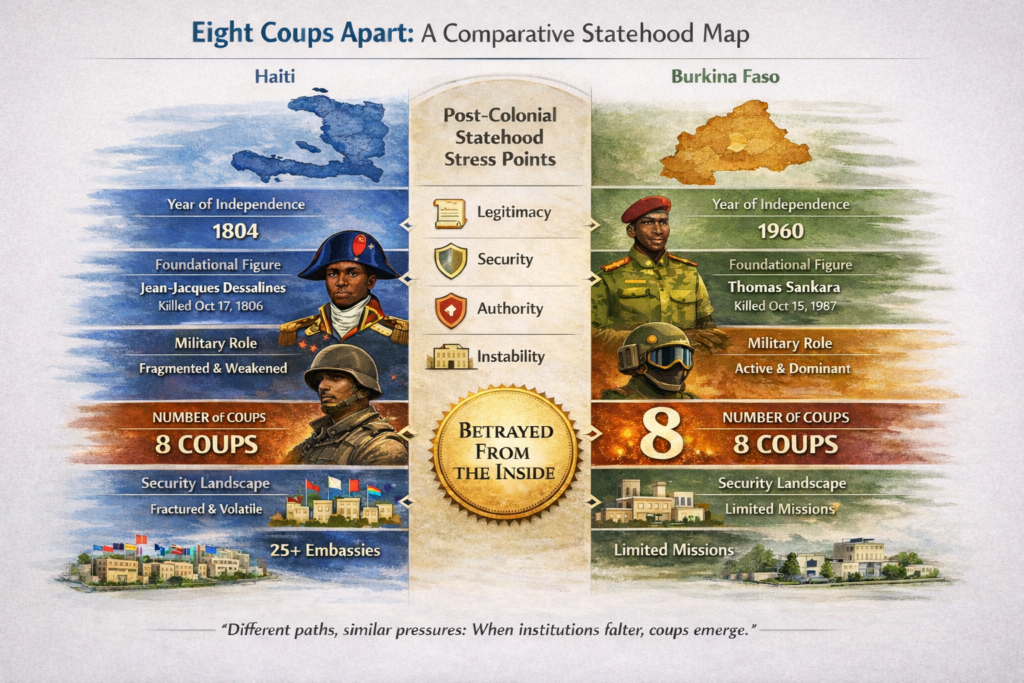

Haiti and Burkina Faso are separated by geography, culture, and historical circumstance. Yet both nations share a striking and revealing parallel: eight successful coups. This symmetry is not accidental, nor does it point to a single external culprit. Instead, it reveals a recurring challenge in post-colonial statehood: how authority is legitimized, how security is governed, and how leadership emerges when institutions fail to absorb pressure.

This comparison becomes clearer when viewed through the lives of those who embodied moments of rupture and possibility. In Burkina Faso, figures like Thomas Sankara and Ibrahim Traoré represent two generations of military leadership shaped by crisis. In Haiti, the nation’s founding figure, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, remains the most powerful reference point for authority rooted in liberation rather than administration.

Together, these figures help explain why coups recur and why, in moments of collapse, societies often look to the military not as a preference but as a last remaining structure.

Independence, Authority, and the Unfinished State

Independence transfers sovereignty, but it does not automatically produce legitimacy. Both Haiti and Burkina Faso emerged into statehood under extreme pressure, with limited economic flexibility and fragile institutional depth. In such conditions, authority is tested not by theory but by survival.

In Haiti, independence followed a total rupture with the colonial order. The new state was born through war, not negotiation. Jean-Jacques Dessalines embodied authority rooted in liberation, unity, and force. His leadership was not administrative. It was existential. The state existed to ensure survival against external and internal threats.

After his assassination, Haiti never fully replaced that foundational authority with a widely trusted civilian alternative. Leadership oscillated between strongmen, elites, and foreign-backed structures, while the military periodically reasserted itself as the ultimate guarantor of order.

In Burkina Faso, independence followed a different path. Authority was inherited through administration rather than revolution. Over time, this produced a state that functioned procedurally but struggled to inspire popular ownership. When institutions failed to respond to inequality or insecurity, legitimacy weakened.

In both cases, the state existed, but belief in it did not fully solidify.

Thomas Sankara and the Military as Moral Authority

The rise of Thomas Sankara illustrates how military leadership can momentarily transcend force and become moral authority. Sankara did not present himself merely as a soldier. He positioned the military as a vehicle for national renewal, discipline, and dignity.

His popularity did not come from coercion alone, but from alignment with public frustration and aspiration. Sankara’s overthrow and death did not erase his impact. Instead, they transformed him into a benchmark. Every subsequent leader in Burkina Faso has been judged, explicitly or implicitly, against what he represented.

This pattern matters. When civilian institutions lose credibility, societies often search for figures who appear decisive, disciplined, and incorruptible. In fragile systems, the military becomes one of the few places where such figures can emerge.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré and the Return of the Soldier-Leader

Decades later, Captain Ibrahim Traoré represents a newer iteration of this dynamic. His rise occurred amid widespread insecurity and frustration with civilian leadership. He did not emerge from ideology, but from urgency.

Traoré’s significance lies not only in his actions, but in what his ascent signals. When security collapses and institutions stall, authority gravitates toward those who promise immediate control and clarity. This does not guarantee success. It does explain recurrence.

Burkina Faso’s repeated coups show that when legitimacy is tied to action rather than process, leadership turnover becomes abrupt and cyclical.

Haiti’s Foundational Figure and the Absence of a Modern Equivalent

Haiti’s situation is distinct yet related. Jean-Jacques Dessalines remains the last Haitian leader whose authority was universally grounded in liberation and collective survival. Since his era, no military or civilian leader has fully occupied that symbolic space.

Modern Haiti has experienced long periods where:

*civilian institutions lacked enforcement power

*the military was dissolved, weakened, or politicized

*security fractured into informal armed actors

*international presence substituted for national authority

This combination creates a vacuum. When authority fragments, people do not stop seeking leadership. They simply stop finding it within formal institutions.

The Embassy Presence and the Authority Paradox

Haiti currently hosts more than two dozen foreign embassies and permanent diplomatic missions in Port au Prince. In theory, such a presence reflects international engagement, partnership, and concern.

Embassies are meant to:

*represent sovereign relations

*support development and humanitarian coordination

*facilitate trade and cultural exchange

*strengthen institutions through cooperation

*protect their nationals

Yet the paradox is unavoidable. A country with extensive diplomatic representation should not simultaneously struggle to exercise basic internal authority. When embassies become long-term crisis managers rather than partners in institutional strengthening, they risk unintentionally reinforcing dependency rather than sovereignty.

This is not an accusation. It is a structural observation. Diplomacy cannot replace legitimacy. It can only support it.

Who Will Be Haiti’s Next Military Leaders

The more responsible question is not who by name, but under what conditions.

If Haiti produces future military leaders, they are likely to emerge when:

*civilian authority continues to lack enforcement capacity

*security remains fragmented

*public trust in political processes erodes further

*sovereignty appears mediated rather than exercised

Such figures would not arise from ambition alone. They would arise from vacuum.

History shows that military leaders do not create instability in isolation. They appear when systems no longer absorb pressure.

What the Comparison Ultimately Teaches

Haiti and Burkina Faso reveal a shared truth about post-colonial statehood. Stability is not guaranteed by independence, constitutions, or diplomatic presence. It is earned through legitimacy, security aligned with civilian trust, and institutions that function in daily life.

Coups are not causes. They are indicators.

Eight coups apart, these two nations remind us that unresolved authority does not disappear. It waits.

Add a comment